Free

October 20, 2010 ~ January 23, 2011

“Free” explores how the internet has fundamentally changed our landscape of information and our notion of public space. Today, our shared space has expanded beyond streets and schools to more distributed forms of collectivity. What constitutes this expanded public is not only greater social connectedness but a highly visual, hybrid commons of information.

SPONSORS

“Free” is made possible by a generous grant from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Major support provided by Shane Akeroyd

Significant support is also provided by the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency, and the Toby Devan Lewis Emerging Artists Fund.

Additional funding is provided by the Mondriaan Foundation, Amsterdam, the Office for Contemporary Art Norway, and the Royal Norwegian Consulate General

Artists

Artist texts were written by Brian Droitcour, Jacob Gaboury, Ceci Moss and Lauren Cornell. Writers are noted on individual texts.

- Liz Deschenes,

- Aleksandra Domanovic,

- Lizzie Fitch,

- Martijn Hendriks,

- Joel Holmberg,

- David Horvitz,

- Lars Laumann,

- Andrea Longacre-White,

- Kristin Lucas,

- Jill Magid,

- Takeshi Murata,

- Hanne Mugaas,

- Rashaad Newsome,

- Lisa Oppenheim,

- Trevor Paglen,

- Seth Price,

- Ryan Trecartin and David Karp,

- Jon Rafman,

- Clunie Reid,

- Amanda Ross-Ho,

- Alexandre Singh,

- Harm van den Dorpel

2010 – Double-laminated inkjet print

The blue screen is a special-effects technique developed by cinema in the 1920s, to place actors in situations that are difficult or impossible to film. This ubiquitous yet invisible technique is the subject of Liz Deschenes’s series “Blue Screen Process,” which traces the blue screen’s evolution through film and television history. Using various photographic techniques to evenly apply color to surfaces, Deschenes achieved results evocative of modernist monochromes, paintings about the materiality of paint itself. But “Blue Screen Process” is less about the immediate presence of color than the infinite possibilities of what could replace it if her blue screens were to be activated. One work from this series, Green Screen #4, is an inkjet print. It simultaneously invokes its origins in the software program that coded its color and the video-editing program that, in a hypothetical future, will chroma key it into oblivion. Deschenes’s display of the artifact suspends the cycle of digital fabrication and erasure at its physical midpoint, a stage that is at once the most concrete and the most replete with possibility.

The blue screen was mainly a media industry tool when Deschenes made “Blue Screen Process” in 2001. Since then, its user base has expanded. Now that it is common for rudimentary video software to come with every home computer, the green screen has become a regular player in homemade skits and pop-culture remixes, which found platforms for distribution in video-sharing sites like YouTube. In the context of “Free,” recent associations like these enter the field of Green Screen #4. Yet the principles of blue-screen technology have hardly changed since its inception, and the work reveals a fundamental aspect of the photographic process that has endured from the Hollywood studio to the personal desktop. -B.D.

Education

Rhode Island School of Design B.F.A. Photography, 1988

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Sutton Lane, Brussels (upcoming)

2010 – Tilt / Swing (version 2), Art|41|Basel – Art Unlimited

2010 – Item, Mitchel-Innes & Nash, New York

2010 – Picture Industry (Goodbye To All That), organized by Walead Beshty, Regen Projects, Los Angeles

2009 – Right/Left, Sutton Lane, Paris

2009 – Chromatic Aberration (Red Screen, Green Screen, Blue Screen – a series of photographs from 2001 – 2008), Sutton Lane, London

2009 – Tilt / Swing, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, NY

2009 – Infinitesimal Eternity, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT

2009 – Color Chart, curated by Ann Temkin, Tate Liverpool, UK

2009 – FAX, The Drawing Center, New York

2009 – Art|40|Basel – Premiere, Liz Deschenes & R. H. Quaytman

2009 – Constructivismes!, curated by Olivier Renaud-Clément, Galerie Almine Rech, Brussels

2008 – Photography on Photography: Reflections on the Medium since 1960, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

2008 – Color Chart, curated by Ann Temkin, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY (Cat.)

2007 – Photographs, Sutton Lane, London

2007 – Registration, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, NY

2007 – STUFF – International Contemporary Art from the Collection of Burt Aaron, Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit, MI

2002 – Modern Photographs from the Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York, NY

2001 – Blue Screen Process, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, NY

1999 – Below Sea Level, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, NY

1997 – Beppu, Bronwyn Keenan Gallery, New York, NY

2010 – 2-channel video, color, sound

By a coincidence of history, widespread internet use came on the heels of socialism‘s collapse in Eastern Europe. Routes of global commerce multiplied in parallel with the speed of information. From today’s standpoint, a world where capitalism and socialism coexisted is associated with rhythms of life defined by slower forms of media. Aleksandra Domanovic considers this condition through her own experience and the history of her native Yugoslavia in 19:30 (2010). The title comes from the time slot of the Yugoslav nightly news, when the whole country would take time to view the broadcast. Watching the news became even more important to the daily routine as ethnic tensions mounted in the late 1980s, but that routine, like many other unifying social norms, dissolved along with Yugoslavia itself amid open conflict. Around 1995, electronic dance music became popular in the former Yugoslavia (a bit later than it did in the rest of the world, due in part to the international isolation of the warring republics) and young people crossed the new borders to attend parties and dance to wordless, repetitive techno—a musical genre free of national associations. When information can be accessed at any time, the nightly news loses the power to create a simultaneous, shared experience for a multitude of people. But a live event like a rave, Domanovic points out, still holds that power.

19:30 is her attempt to reconcile past and present. Last year Domanovic traveled around the former Yugoslavia to collect idents, the graphical introductory sequences that precede news broadcasts. Her research process involved visits to television stations, national archives, and even peoples’ homes, and resulted in an extensive collection of idents, annotated with historical details. After assembling the collection, Domanovic reached out to techno DJs and asked them to use the idents as samples and mix them in their music.

19:30 highlights how the nature of shared experience has changed and unites two disparate models of it. Domanovic‘s collectionof digitized idents isn’t an archive, a graveyard for dead scraps of history, but an active library, where audible pieces of public memory gain new life. Through remixing and live performance, the old melodies become free, like bodies given over to dance. -B.D.

Education

Faculty of Architecture, University of Ljubljana 2000 – 2001

University of Applied Arts, Vienna 2001 – 2006

Selected Exhibitions

2011 – 19:30, Museum of Yugoslav History, Belgrade

2010 – From Abstract to Activism, Eternal Tour, Jerusalem

2010 – Free, The New Museum, New York

2010 – Shift, Basel

2010 – 255.804 km2, City Art Museum, Ljubljana

2010 – Surfing Club, Plug.in, Basel

2010 – Bidoun Magazine Video Screening, Art Dubai, Dubai

2010 – Noise Not Noise (http://front.nfshost.com/noisenotnoise/), The Western Front

2009 – Session_7_Words, Am Nuden Da, London

2009 – AFK Sculpture Park, Atelierhof Kreuzberg, Berlin

2009 – Image Search, P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

2009 – Padiglione Internet, collateral event of the 53rd Venice Biennale, S.A.L.e, Venice

2009 – Doing Boundless, Platform 3, Munich

2009 – BAKSPEILET, Rogaland Art Centre, Stavanger, Norway

2009 – Yebisu International Festival for Art and Alternative Visions, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo

2009 – Ours: Democracy in the Age of Branding, The Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, New York

2009 – http://www.nobelprize.no/, curated by: Aeron Bergman & Alejandra Salinas

2009 – http://mybiennialisbetterthanyours.com/, curated by Tolga Taluy, 14.9.2009 – 31.12.2009

2009 – The Painting Show, Gallery Art Since The Summer of 69, Private Circulation PDF, April 2009

2008 РShift, Dreispitzhalle Basel/Münchenstein, Basel

2008 – Tomorrow is Humorless, Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam (SMBA), Amsterdam

2008 – Videomedeja, The Museum of Vojvodina, Novi Sad

2008 – First Selection, Curated by Harm van den Dorpel, www.clubinternet.org, 8.5. – 14.6. 2008

2008 – ORACLE, Curated by Harm van den Dorpel, www.clubinternet.org, 16.6. – 17.7. 2008

2008 – Contact (1997), Curated by Damon Zucconi, www.clubinternet.org, 25.7. – 19.8. 2008

2007 – Ursula Blickle Videopreis 2007, KUNSTHALLE WIEN, Vienna

2007 РProjections Series: Darren Almond and Music Video, Museod‘art contemporain de Montreal

2006 – Wired Women of Whitechapel, Whitechapel Gallery, London

2006 – Nemaf (Seoul New Media Festival), Seoul

2006 – Chicago Underground Film Festival, Chicago

2010 – In collaboration with Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, and David Toro for DIS, Ryan Trecartin and Telfar Clemens.

Bed Frame, wood, windows, clothing, printed material, globe, purses, belts, rocks, sand, paint, clothing rack, plaster, foundation, nails, gloves, eyelashes, pillows, shoes, hangers, video cameras, hammer, tupperware, clothespin, plastic

Today, often the most social parts of our lives take place in our bedrooms at a remove or, as the artist writes “through windows.” Pangea, a new sculpture by Fitch, literalizes the ways in which computers have collapsed the boundaries of our personal and public space. Fitch, a sculptor whose work pivots on identity, creates large-scale assemblages out of found objects through a process that resembles the digital-effects tool Photoshop in its rampant copying, pasting, and reshaping. Her materials are often sourced from the realm of lifestyle merchandise and branding. She picks and chooses clothing or accessories that signify a certain class, gender, or culture and then inverts them by ripping them out of their context.

Fitch often works with other artists, and some of her main collaborators contributed to Pangea. DIS Magazine, a multimedia art magazine, presents original jewelry to adorn underwear, along with shoes, and a set of terra-cotta-colored undergarments; fashion designer Telfar has outfitted original hangers; and artist Ryan Trecartin, featured separately within “Free,” has placed a two-screen video recording device underneath the bed that—instead of shooting from one angle—captures exchange between viewers observing the sculpture. All video captured through this camera will be streamed live onto DIS Magazine’s website: dismagazine.com.

Represented in the gallery and online (through the DIS website), Pangea pushes the privacy of its own solitary location within the gallery. -L.C.

2008 – Video, black and white, silent, 8:48 min

Martijn Hendriks describes his 2008 Untitled Black Video as a reconstruction of a leaked cell phone video of the 2006 execution of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. Paradoxically, his reconstructive process removed the footage from the frame entirely, replacing it with anonymous reactions from various online chat forums where the video was posted. Hendriks is interested in how the use of digital effects might correct a discrepancy between the appearance of images and their cultural meaning. His previous explorations of this idea have involved running paparazzi photos of Britney Spears through atmospheric filters to

make them more mysterious and ambiguous, and erasing the eponymous threat of The Birds from each frame of the eponymous movie—a result that could be considered a more effective visualization of Hitchcock‘s concept of pervasive, overwhelming, inexplicable fear.

Untitled Black Video carries Hendriks’s inquiry into the realm of politics and history, by presenting reactions to a historical moment as an alternative form of documentation. With its appropriation of typical internet chatter, Untitled Black Video gives voice to the idiosyncratic media literacy characteristic of contemporary visual culture, and the attitude of irreverent dismissal it breeds. Yet the work has an air of solemn mystery befitting the historic import of Hussein’s execution. When the mass distribution of an image implicitly subjects it to defacement, belittlement, or (worse yet) indifference, what can an artist do to assert an image‘s significance? In Untitled Black Video, Hendriks offers one suggestion: Make it disappear. -B.D.

Education

University of Maastricht, 2002

Academy of Fine Arts Tilburg, 1994

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Turned into nothing before leading into everything, RSTR4, Munich, DE

2010 – Smooth Structures, Smart Project Space, Amsterdam

2010 – Be Blue, Laleh June Galerie, Basel

2010 – Fotografia, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma, Rome

2010 – Catalyst, American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, Washington DC

2010 – Video Feedback, Hunter Times Square Gallery, New York NY

2010 – The Destroyed Room II, Whatspace, Tilburg

2010 – The Destroyed Room I, Galerie im Regierungsviertel / Forgotten Bar Project, Berlin

2010 – Whole Earth Catalogue, Neoncampobase, Bologna

2009 – Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off, MIC Toi Rerehiko, Auckland

2009 – Versions, Netherlands Institute for Media Arts Montevideo/Time Based Arts, Amsterdam

2009 – Imagine, CasZuidas, Amsterdam

2009 – New Wave, Padiglione Internet, 53rd Venice Biennale, Venice

2009 – Michael Jackson Doesn’t Quit, The Future Gallery, Berlin

2009 – Contemporary Semantics Beta, Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam

2008 – When Absence Becomes Presence, Washington Project for the Arts, Washington DC

2008 – The Birds without the birds, Broadway Media Centre, Nottingham

2008 – Drawing near, then away, FADA Art Gallery, Ankara

2008 – Always on your minds, Video Vortex 3, Ankara

2008 – Netmares/Netdreams, Current Gallery, Baltimore MA

2007 – Video Vortex 2, Netherlands Media Art Institute Montevideo/Time Based Arts, Amsterdam

2007 – Video as Urban Condition, Lentos Kunstmuseum/Museum of Modern Art Linz, Linz

2007 – Untitled Group Show, Atelierhaus, Aachen

2007–10 – 10 panels, printed Sheetrock

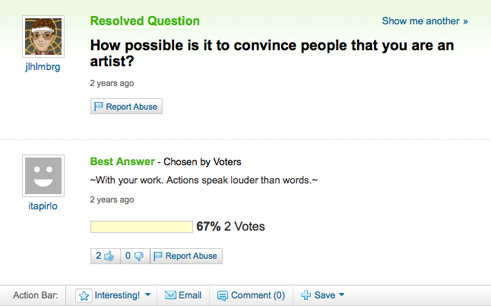

Joel Holmberg’s work explores how behavior, environments, and objects translate online. Many of his projects center around online experience, and the ways people can both participate in and reject commercial systems provided to them. Projects, like Legendary Account, foreground corporate structures, and throw them off with witty disobedience.

Legendary Account (2007–10) involves the artist asking profound, existential questions in the user-generated forum Yahoo! Answers, which requires users to select categories like “Pets” or “Home Maintenance” before posting. It is

commonly used for questions like “Where is the nearest pet store?” Holmberg’s questions—including “How does it feel to be in love?” or “How do I best convince someone I am an artist?” or “How do I occupy space?”—subvert the simple Q&A service. They are too searching, too complex; they tease the system of Yahoo! Answers and challenge commenters to interpret and grapple with philosophical questions. The work exists both online, in a series of answers on Holmberg’s Yahoo! Answers account. Here, the questions are installed as scrolls against a background that matches the background of the Yahoo! Answers site.

Education

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, BFA August 2002 – May 2005

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Bidoun Video Program, Art Dubai, Dubai, UAE

2010 – Surfing Club, Plug-in, Basel, CH / Espace Gantner, Belfort, FR

2010 – Multiplex, Sun Gallery, Munich, DE

2010 – Made in Internet, Artboom Festival, Krakow, PL

2010 – Bidoun Video Program”, Townhouse Gallery, Cairo, EG

2009 – Woman Eating Grapes / Empty Pockets (Roullete Wheel), Clockwork Gallery, Berlin, DE

2009 – Totale Erinnerung, Alter Meßplatz, 3rd Fotofestival in Mannheim, Mannheim, DE

2009 – Away From Keyboard Sculpture Park, Atelierhof Kreuzberg, Berlin, DE

2009 – Nasty Nets, Sundance Film Festival, Park City, UT, USA

2009 – Distributed Gallery, Telic Arts Exchange, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2008 – Dallas Video Festival, Conduit Gallery, Dallas, TX, USA

2008 – Nasty as U Wanna Be, New York Underground Film Festival, New York, NY, USA

2007 – Professional Surfer, Rhizome.org at The New Museum, New York, NY, USA

2006 – Free Wireless, Harvey Levine Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA

2005 – Circuit, Eyebeam, New York, NY, USA

2005 – Hypertemporality, Marsh Art Gallery, University of Richmond Museums, Richmond, VA, USA

2010 – Newsprint and book

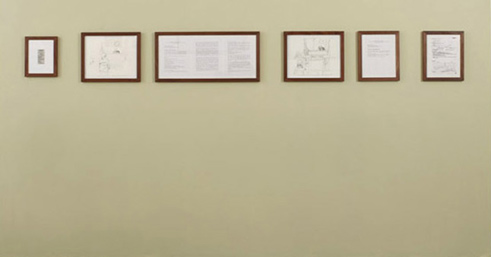

David Horvitz’s work spans photography, performance, sculpture, and print media. Recurring interests across these disciplines include attention to strategies of information circulation and the impermanence of digital artifacts. From the Southern-most Inhabited Island of Japan (Hateruma… Public Domain) is an extension of A Wikipedia Reader, a multi-artist publication and project Horvitz organizes and publishes with the designer Mylinh Nguyen.

A book released in multiple installments, A Wikipedia Reader presents trails of interlinking Wikipedia articles that have been made by contributors, providing the reader with a casual portrait of their thought process as they browsed this massive database.

Inspired by A Wikipedia Reader, From the Southern-most Inhabited Island of Japan (Hateruma… Public Domain) tracks the artist’s travel to the Japanese island Hateruma, and parallels it with the journey of an image through Wikipedia from the entry “Hateruma” to “Public Domain.” The installation includes images from these entries, which also include original photographs by the artist that he uploaded, to mix his own personal recollections into the public picture of the places he passed through. The images have been assembled sequentially, following the path of his journey; his trail begins and ends with the public domain, from the initial photograph of Hateruma by Horvitz that he posted to the island’s entry, and its conclusion with a shot of Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (a book famously not copyrighted) taken from the Wikipedia page for the Public Domain. The images presented in From the Southern-most Inhabited Island of Japan (Hateruma… Public Domain) depict Horvitz’s travel through its online representation. -C.M.

Education

Milton Avery Graduate School of Arts Bard College 2010

University of California at Riverside 2004

Exhibitions

2010 – Carry On, Gallerie West, Den Haag, Holland

2010 – Kiosk, Golden Parachutes, Berlin, DE

2010 – Palling Around with Socialists,U·turn Art Space, Cincinnati, OH

2010 – No Soul For Sale, Tate Modern, London

2010 – We Have as Much Time as it Takes,Wattis Institute, San Francisco, CA

2009 – Young Collectors #1, Sign, Groningen, Holland

2009 – Get Free, Golden Parachutes, Berlin, DE

2009 – Evading Customs, Brown, London

2009 – Unintended Uses, Nexus, Philadelphia, PA

2009 – The Wild So Close, Or Gallery, Vancouver

2009 – Rarely Seen Bas Jan Ader Film, 2nd Cannons, Los Angeles, CA

2008 – Cycling Apparati, High Energy Constructs Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2008 – Line Up, Strip Down, Fade Out, Vanderbilt University Gallery, Nashville, TN

2007 – Between Thought and Expression, Sweeney Art Gallery, Riverside, CA

2010 – Video projection

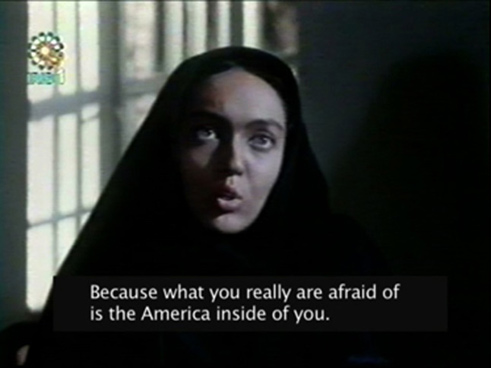

Lars Laumann uses video to explore alternative realities and histories. Helen Keller (and the great purging bonfire of books and unpublished manuscripts illuminating the dark) is a video essay in two parts. It uses a range of techniques and approaches to discuss filmic and literary adaptation, multiple narratives, censorship, and the burning of books. The first part, “Kari & Knut,” is based on the texts of Helen Keller. Born in Alabama in 1880, Keller was an author, lecturer, and political activist; she was blind and deaf—she lived in complete darkness and silence. The video uses found footage from an Iranian adaptation of J.D. Salinger’s 1963 story Franny and Zooey to retell two of her works, The Frost King and How I Became a Socialist, which brought her accusations of plagiarism.

The second part is a collage of found and produced elements. It revolves around a 1960s adaptation of the Swedish author Selma Lagerlof’s novel, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils. Published early in the twentieth century, the novel tells the story of Sweden’s history and geography. It was written for children but became one of the most popular Swedish books of the last 100 years. Lagerlof covers all the different parts of Sweden except Halland, an area in the southwest. Many people believe Lagerlof omitted Halland because she saw it as ”racially impure. ”Lagerlof was involved in (and financially supported) racial biology research in its early stages. This second part features a new music track called “It’s Grim Out West” by Dan Ola Persson, whose background is in Scandinavian black and death metal. The work’s central theme is censorship: Lagerlof ”censored” Halland; Keller was censored around copying and for political reasons; Salinger censored himself. Salinger continued to write but did not publish after 1964 and refused all adaptations of his work. -L.C.

Education

Norwegian State Academy, Oslo, Norway 1995-2001

North Norwegian Art and Film School, Kabelvåg, Norway. 1993-1995

Exhibitions

2010 – Kunsthalle Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland

2010 – Maureen Paley, London, UK

2010 – Foxy Production, New York, NY

2010 – Bunkier Sztuki, Krakow, Poland

2010 – Liverpool Biennial, Liverpool, UK

2010 – Mediations Biennale, National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

2009 – Forth Worth Contemporary Arts, Forth Worth, TX

2009 – Galway Arts Festival, Galway Arts Centre, Galway, Ireland

2009 – Trænafestivalen, Træna, Norway

2009 – Momentum 5th Nordic Biennial of Contemporary Art, curated by Lina Džuverović and Stina Högkvist, Momentum Kunsthall and Galleri F15, Moss, Norway

2009 – Report on Probability, curated by Adam Szymczyk, Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, Switzerland

2009 – The Reach of Realism, curated by Ruba Katrib, Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, Miami, FL

2008 – 5th Berlin Biennial, curated by Adam Szymczyk and Elena Filipovic, Berlin, DE

2008 – Medium Cool, curated by Hanne Mugaas, Art in General, New York, NY

2007 – “Morrissey Foretelling the Death of Diana”, curated by Matthew Higgs, White Columns, New York, NY

2007 – Morrissey Foretelling the Death of Diana”, Vox Populi/SCREENING, Philadelphia, PA

2007 – East International, curated by Matthew Higgs and Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Norwich Gallery, Norwich

2007 – Peer in Peer Out, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, AZ; and The Moore Space, Miami, FL

2006 – The Thick Plottens, Galuzin Gallery, Oslo, Norway

2006 – Entre Chienne et Louve*, Le Commissariat, Paris, FR

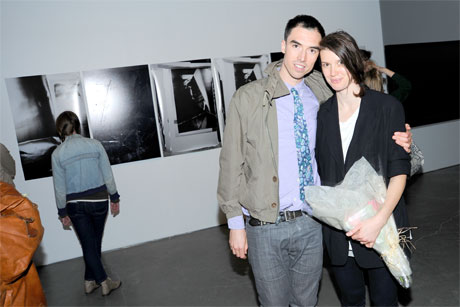

2010 – Archival inkjet prints

The photographs on display by Andrea Longacre-White include work from two series, entitled “Dark Current” and “Black Outs.” Both take their names from technical terms used in digital photography: “Dark Current” refers to the irregularities that can occur during an image‘s translation into digital content; “Black Outs” to a process whereby the artist’s shooting speed surpasses the flash’s capacity to recharge, resulting in a flash-less recording. Longacre-White uses these conditions of potential failure as a departure point for works that explore the lack of transparency or intelligibility in photographs, even when enabled by the highest production tools. Each work begins with a stock low-resolution photograph—in this case, images of car accidents that the artist found in response to a nagging vision that she herself would be involved in a car accident en route to get prescriptions for her dying father—that is then shot and re-shot in the artist’s studio, blurring the original image out of recognition, making it almost impossible to track or locate. Contemporary imagery is often subjected to endless reproduction and re-presentation, as it cycles through different contexts. Here, the artist speeds up the image’s evolution by submitting it to generations of re-shooting and re-framing in her studio. Applying different frames to the image, and capturing different surfaces, Longacre-White brings out the photograph’s materiality, its tangible presence and flaws—a far cry from the ephemeral state in which the photograph was first found. -L.C.

Education

Hampshire College, Amherst, MA, BFA, 2003

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Solo Exhibition, Rental Gallery, New York, NY

2010 – Substance Abuse, Leo Koenig Projekte, New York, NY

2010 – Ashes to Ashes, AMP Gallery, Athens, Greece

2009 – Not Fair, Oh Wow Space, Miami, FL

2009 – Ooga Booga Reading Room, The Swiss Institute, New York, NY

2008 – And Then, What Then: Photography Show, Capricious Space, Brooklyn, NY

2008 – Every Picture Tells A Story… Or At Least Is A Picture, Curated by Jo Jackson and Chris Johanson), , Small A Projects, Portland, Or

2008 – I Do Adore, Receiver Gallery, San Francisco, CA

2007 – Tiny Vices Show, Curated by Tim Barber, Spencer Brownstone Gallery, New York, NY

2007 – Red White and Blue, Spencer Brownstone Gallery, New York, NY

2007 – 6 sections: newspaper announcement, two pencil drawings by Joe McKay, two court transcripts, and decree-changing name

New technology doesn’t just offer new conveniences; it also equips us with new metaphors. In 2007, Kristin Lucas told a judge she wanted to legally change her name from Kristin Sue Lucas to Kristin Sue Lucas, in order to refresh herself as though she were a web page.

The term “refresh” entered the computing lexicon as a metaphor in the 1960s, to designate the act of updating a memory device. In the 1990s it became a fixture of web browsers. Lucas’s back-translation of the term to the human realm puts a tech-inflected spin on the philosophical problem of change, contested at least since Parmenides’s proposition, more than two millennia ago, that an entity remains the same as long as the language used to name it does. When you click a refresh button, the browser sends a query to the server hosting the web page you‘re looking at and returns with new information, if there is any. The notion of versionhood suggests that the essence of identity—the soul, if you like—is remote and unseen, like a host server, and a person is its visible, tangible manifestation, its interface. And even as a person changes, her link to her essential self is as constant as a domain’s connection to its IP address.

Lucas has identified herself with telecommunications technologies before. In her 1996 video Cable Xcess, she claimed to transmit a broadcast through her body, as though it were a satellite; her message was a public-service warning about the negative consequences of long-term exposure to television‘s electromagnetic fields. The online project Between a Rock and a Hard Drive prompts viewers to imagine themselves in a “waiting room” inside a computer as it loads data over a slow connection. Through the parallel she draws between people and devices, Lucas offers insight into how the pervasiveness of technology has subtly changed our perceptions of the world and ourselves. -B.D.

Education

The Cooper Union 1994

Stanford University 2006

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Seven on Seven, The New Museum, New York, NY

2009 – The Future Is Not What It Used To Be, Postmasters Gallery, New York, NY

2009 – Variety Evening, The New Museum, New York, NY

2008 – Kristin Lucas: Show #14, And/Or Gallery, Dallas, TX

2008 – Record, Record, Shift Electronic Arts Festival, Basel

2008 – Off The Grid, Neuberger Museum of Art, White Plains, NY

2007 – If Then End Else If, Postmasters Gallery, New York, NY

2007 – Automatic Update, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

2006 – if lost then found, Or Gallery, Vancouver

2006 – No Place, Cheekwood Museum of Art, Nashville, TN

2005 – Brides of Frankenstein, San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

2005 – Balance of Power: Performance and Surveillance in Video Art, Krannert Art Museum, Champaign

2004 – Fly Utopia!, Transmediale.04, Berlin, DE

2004 – New Acquisitions, The Museum of Modern Art, Queens, NY

2003 – Celebrations for Breaking Routine, Foundation for Art & Creative Technology, Liverpool, UK

2003 – Celebrations for Breaking Routine, Plug.in, Basel, Switzerland

2003 – Web as Performance Space, Institute of Contemporary Art, London, UK

2001 – The Electric Donut, The New Museum of Contemporary Art Media Z Lounge, New York, NY

2001 – Animations, P.S.1 Contemporary Art, Queens, NY

2001 – Drama Queens, Guggenhiem Museum, New York, NY

2001 – Body as Byte,New Kunstmuseum, Luzern

2000 – Temporary Housing for the Despondent Virtual Citizen, O.K Center for Contemporary Art, Linz

1997 – The 1997 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

1997 – Young and Restless, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

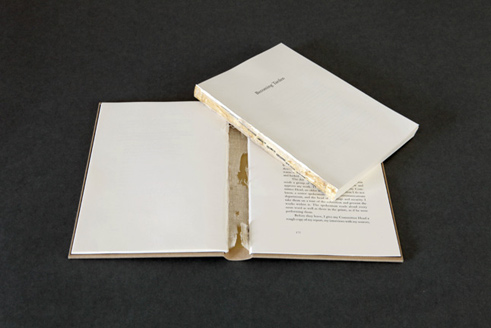

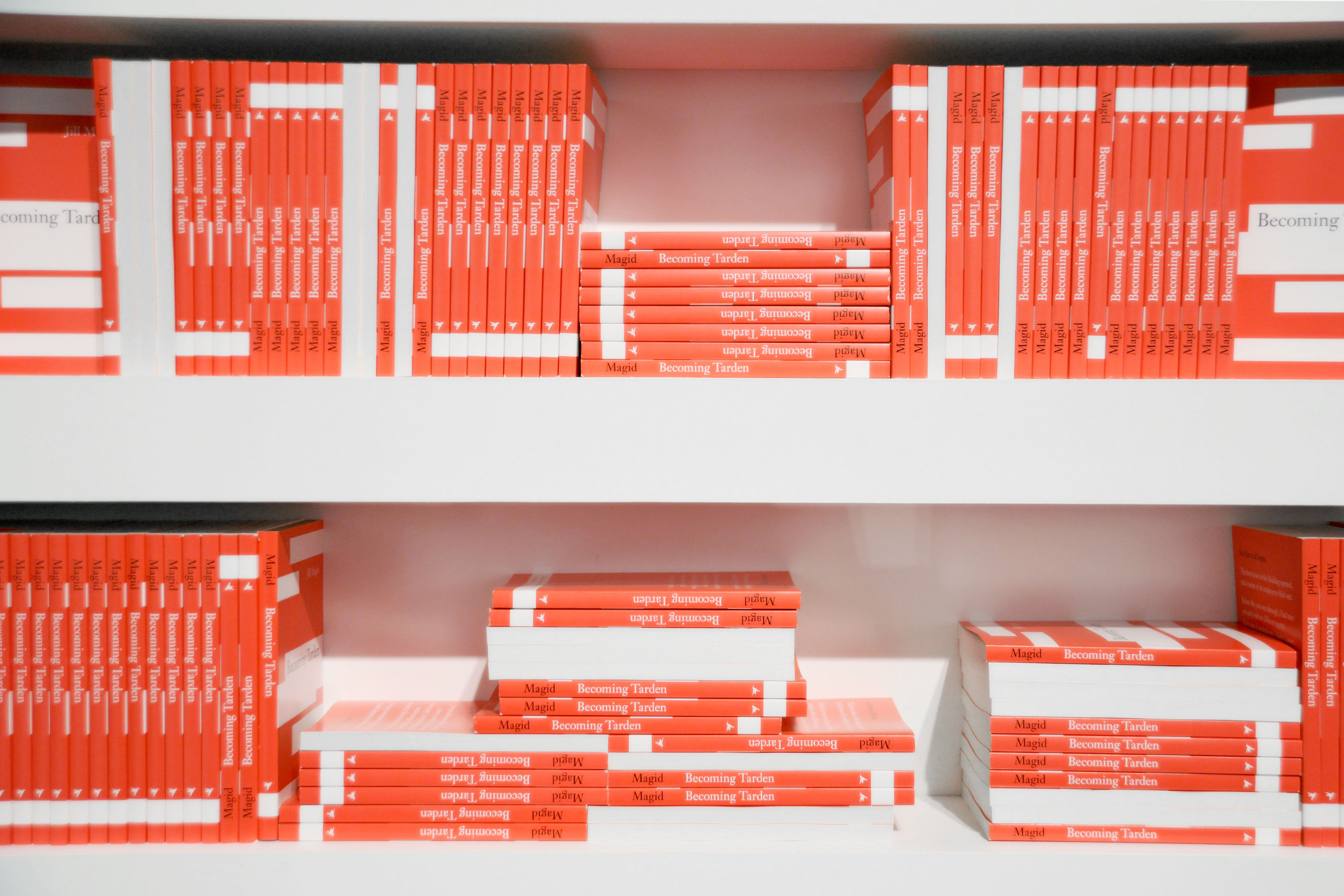

2010 – Paperback books, hardcover book, and document

In 2005, artist Jill Magid was commissioned by the Dutch secret service (AIVD) to create a work that would reveal the human face of the organization. During the next three years she met with eighteen agents who volunteered to be interviewed, but remained anonymous even to her. The project resulted in a variety of forms, among them a novel called Becoming Tarden—Tarden being a character in Polish-American novelist Jerzy Kosinski’s book Cockpit, an agent (a “hummingbird”) whose real identity is kept from other agents and is often disguised as a cultural official, a businessman, an artist, or writer. Up to 40 percent of Magid’s manuscript was censored by the AIVD, as they felt their methods and the identities of their agents were being exposed. After negotiations with the organization, Magid agreed to let them seize the uncensored body of the book after being exposed—under glass and out of reach—from the Tate Modern in London earlier this year. She retained for herself only the prologue and the epilogue. The paperback edition of Becoming Tarden shown here includes the redactions of the Dutch government.

Becoming Tarden resonates with Magid’s larger body of work, which involves the infiltration of closed systems and the turning of surveillance back on itself. For instance her project LOVE, in which her request for a cop to search her post-9/11 New York, became the basis of a long relationship in which she surveyed the MTA’s inner workings. -L.C.

Visitors are encouraged to remove and read books from the lower shelf. We ask that you return them in the place you found them.

Books are available for purchase in the New Museum Store.

2010 – Single-channel video, 6 min – Sound design and music by Devin Flynn and Ross Goldstein

In Europe, Popeye’s copyright expired on January 1, 2009, which means his likeness can be used in comics, on clothing, and elsewhere without authorization from the copyright holder—but only in Europe, where the law protects copyright for seventy years following the author‘s death (E.C. Segar, who first drew the spinach-guzzling sailor in 1929, died in 1938). In the United States, however, copyright stands for ninety-five years after it is first registered, so uses of Popeye will have to be registered through 2024. The discrepancy in US and EU law has created an odd situation where geography determines legal constraints on the production of highly mobile images.

Takeshi Murata wasn’t aware of the copyright issue when he began working on I, Popeye (2010), but it highlights the contradictions that interest him: the possibility of “unauthorized use” with images that are as deeply embedded in the popular consciousness as a song like “Happy Birthday.” Here, Murata twists a cartoon of heroic triumph into a litany of failure—the opposite of what Disney does when adapting a tale that, in the Grimms’ telling, doesn‘t end happily. The halting, minor-key version of the Popeye theme song in Devin Flynn and Ross Goldstein‘s soundtrack and the leering, moneyed Popeye pictured on the anti-hero‘s T-shirt—a caricature of pop-culture icon as commodity—are two details that contribute the video‘s effect. But the key factor is the medium itself. By rendering the characters in the kind of slick three-dimensional animation commonly associated with big-studio production, Murata intensifies and complicates the discrepancy between the official Popeye and his own “folk” version. -B.D.

2010 – Mixed-medium installation

Hanne Mugaas is a curator whose exhibitions cross over into the terrain of art, and can often be understood as artworks. Her projects are inspired by the impact of the internet on visual culture and often manifest in transitory spaces, such as PDF files, websites, one-night exhibitions, and screenings. She is the co-founder of Art Since the Summer of ’69, a six-by-six-foot gallery housed in the former cleaning closet of the 195 Chrystie building, around the corner from the New Museum. The project on view here, Secondary Market (2010), is an assemblage of items that Mugaas has sourced from the online auction site eBay. The term secondary market refers colloquially to the backroom of galleries, and literally to the resale of contemporary artworks, usually after the work in question has increased in value. As a platform for buying and selling used items, eBay follows this same model, except its audience is the larger public, rather than collectors, galleries, and auction houses. Mugaas purchases new items for each version of the work here. In the past objects such as shopping bags that repurpose Picasso’s paintings as a design motif or T-shirts with repetitive patterns lifted from Andy Warhol have been included. Secondary Market, in both its name and concept, spotlights how art is translated outside of its primary market, and adopted and even re-created by popular culture. It acts as a small exhibition of art as it is popularly bought and sold—not through gallery backrooms, but on eBay. -C.M./L.C.

Status Symbol #31 2010 – Collages on paper with frame

Rashaad Newsome creates powerful, original collage and performance through composite parts. His practice is based in sampling and he is interested in the ways picking apart and recombining culturally specific material, like a hip-hop track, can, in the artist’s words, “elicit emotional and visceral responses that can be universally recognized and felt.” His work spans performance, sound, video and collage—all of which are tightly composed and choreographed

Status Symbols #31 and Status Symbols #35 are part of Newsome’s “Coat of Arms” series through which he blends eighteenth-century heraldry with today’s pop culture and bling. In #31, merchandise from the rap impresario Jay-Z mingles with ornate jewelry; in #35, the singer Nicki Minaj is perched atop an amalgamation of weapons and jewelry. Sourced from the web, the images have been lifted and resized—their original shape and context lost—so that they can meld within a new cultural emblem. In bridging heraldry with pop cultural and hip hop references—all ensconced in wild amounts of bling—Newsome intermingles, and erases, notions of high and low culture.

Newsome’s previous works have similarly explored identity and culture by bridging diverse traditions and technologies. Shade Compositions (2009), which first premiered at The Kitchen in New York, is a vibrant improvisational performance, which features a chorus of more than twenty black women. Newsome conducted them—divided into groups akin to instrumental sections as they performed sequences of culturally specific or stereotypical gestures, movements, and vocalizations—and at the same time, recorded, mixed and looped it with a Nintendo Wii controller. The video The Conductor weaves a composite of popular hip-hop tracks sourced from New York radio stations Hot 97 and 105.1 in and out of Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana” in six parts.

2006 – 35mm slide projection

For The Sun is Always Setting Somewhere Else (2006), Lisa Oppenheim sourced pictures of sunsets from the image-sharing website Flickr taken by US soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan, and then re-photographed them against her own horizon in Manhattan. The work frames a shared, unspoken tendency to connect to a universal experience from a foreign vantage point. As with other works by Oppenheim, The Sun is Always Setting Somewhere Else takes seemingly minor aspects of visual culture, and teases out their deeper meaning, demonstrating how they point to larger events. In the case of The Sun is Always Setting Somewhere Else, the larger event is war, and a yearning for human connection or purpose within displaced and challenging circumstances. Oppenheim‘s work involves much time spent looking for artifacts or images that illuminate larger histories or contemporary situations. Her work begins with material found in archives, magazines, or the web, and manifests in a wide range of forms depending on her original subject matter, from 16mm film, to photography, prints, and drawing. -L.C.

2010 – C-print

Trevor Paglen is an artist, writer, and experimental geographer working in New York City and Oakland, CA. For the past eight years Paglen has explored the “black world” of secret military operations, publishing critical texts, image collections, and photography documenting the objects that make up this unseen world. While images in Paglen’s work may at first appear simple or commonplace, they in fact reveal that which is hiding in plain sight. Working with amateur astronomers, plane spotters, and other online communities of often-anonymous individuals, Paglen gains insight into the secrets of this “black world” and visualizes them in these subtle but striking images.

In They Watch the Moon, 2010, Paglen captures a surveillance station run by the NSA and the Navy in a part of West Virginia known as the US National Radio Quiet Zone, in which no electromagnetic radiation is permitted. While officially this is to prevent interference with the nearby Green Bank Observatory, it also services this radio telescope spying station, which was originally constructed to pick up telephone and other radio signals on the other side of the planet as they are transmitted out into space and bounce off of the moon. Paglen captures the site at night, glowing under the light of a full moon.

In Dead Military Satellite (DMSP 5D-F11) Near the Disk of the Moon (2010), Paglen captures a dead military satellite as it is about to cross the disk f the moon. Before they were commonplace, satellites were often referred to in laymen’s terms as “artificial moons.” Similarly the moon is one of many forms of “natural satellites,” in that it is a celestial body that orbits a larger, primary body.

In PAN (Unknown; USA-207), an array of stars is made visible using time-lapse photography as they streak across the night sky. Looking closer toward the center of the image there is a cluster of stationary dots that do not move along with the other stars. These are communications satellites that have been positioned in a narrow ring of orbit called the Clarke Belt, in which objects move at the exact speed of the earth‘s rotation and thus appear stationary above a particular global point. While these satellites are used for all kinds of communication, both commercial and military, the second dot from the left of the central cluster is a secret, unregistered satellite known as Pan, or Palladium at Night, hovering above Somalia and the Middle East. The image was captured in South Africa with the aid of amateur astronomers.

Finally, Untitled (Predators; Indian Springs, NV) from 2010 captures two military predator drones as they fly across the sky during training exercises sixty miles northwest of Las Vegas.

-J.G.

Essay with Knots, 2008 – Screenprint on high-impact polystyrene and ropes; 9 parts

Essay with Knots is one manifestation of Dispersion, an open-ended work Price started in 2002, that takes the form of a widely reproduced essay, an artists’ book, a freely available online PDF, as well as the sculpture on view. Price adjusted and tweaked Dispersion over a decade, leaving it perpetually unfinished, in an open state. In the essay, Price discusses attempts by conceptual artists to circumvent the structures of the art world and the art market by co-opting the distribution-oriented, communicative media associated with popular culture, and how these works have, to some extent, been thwarted by art history’s tendency toward archive and provenance. The tone shifts from authoritative to personal, swinging back and forth from proclamations to doubt. Price’s examples include Marcel Duchamp, Dan Graham, and Seth Siegelaub, but he was also referring to his own work: his essays, music mixes, and Dispersion itself.

Essay with Knots turns the text of Dispersion into sculpture made of vacuum-formed plastic, a material used to package mass-produced goods. The packaging is empty, a trace for a product that is shapeless and absent; the question is whether that’s enough to make a convincing connection between the static object and the digital file, a questioned raised by Price in the essay: “An art that attempts to tackle the expanded field, encompassing arenas other than the standard gallery and art world circuit, sounds utopian at best, and possibly naïve and undeveloped. . . . .” He continues, “But hasn’t the artistic impulse always been utopian, with all the hope and futility that implies?”

Dispersion is cited as an inspiration for “Free” for the above ruminations, and also for Price’s consideration of a new form of publicness: “We should recognize that collective experience is now based on simultaneous private experiences, distributed across the field of media culture, knit together by ongoing debate, publicity, promotion, and discussion. Publicness today has as much to do with sites of production and reproduction as it does with any supposed physical commons, so a popular album could be regarded as a more successful instance of public art than a monument tucked away in an urban plaza.” In an exhibition examining the evolution of an expanded culture, Price’s grappling with changes the web has wrought to art, and the expansion of public space, is an essential touchstone.

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Capitain Petzel, Berlin, DE

2010 – Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, DE

2010 – Meet Me Inside, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA

2009 – Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York, NY

2009 – Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Bologna, IT

2009 – Besides, With, Against and Yet: Abstraction and the Ready-Made Gesture, The Kitchen, New York, NY

2009 – Altermodern, Tate Triennial, London, UK

2008 – Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

2008 – Kunsthalle Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

2008 – Koelnischerkunstverein, Cologne, DE

2008 – Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY

2008 – Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, UK

2007 – Modern Art Oxford, Oxford, UK

2007 – Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, DE

2007 – A Fair Show: Slang and Cool Orthodoxy, Massimo de Carlo, Milan, IT

2007 – Lyon Biennial, Lyon

2006 – Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY

2006 – Reena Spaulings, New York, NY

2006 – Electronic Arts Intermix, New York, NY

2006 – Galerie Isabella Bortollozi, Berlin, DE

2006 – Gold Standard, P.S.1, New York, NY

2006 – Grey Flags, Sculpture Center, New York, NY

2005 – This is Not an Archive, The Center for Curatorial Studies, New York, NY

2005 – Greater New York, P.S.1, New York, NY

2004 – Autumn Catalogue: Leather Fringes, Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, Switzerland

2003 – In Light, Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario

2003 – Playground, Galleria Emi Fontana, Milan, IT

2003 – 25th Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts, curated by Christophe Cherix, Ljubljana

2002 – Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

2002 – Project Room, Artists Space, New York, NY

2002 – Playground, CAN, Neuchatel

Programming and design by Nick Hasty and Sergio Pastor.

2010 – Video project, streaming live from the web at riverthe.net

A dynamic, open website that allows users to upload ten-second videos with three identifying tags, riverthe.net may be viewed streaming live off the web as a continuously generated playlist, transitioning from one video to the next based on related tags. The result is a rapid-fire, associative stream of video that allows viewers to cycle through clips produced through the collaborative efforts of anonymous users. River the Net was developed through Seven on Seven, a conference organized by Rhizome, which paired artists with technologists to create new work.

Ryan Trecartin is an artist currently working in Philadelphia, PA. Trecartin’s videos are an exploration of space, identity, technology, and culture in an assemblage of color, video effects, and slang. Much of his work is temporally and otherwise abstracted to produce what Trecartin describes as an alternate mode of viewing: one that is both reflective and emotional, asking viewers to let each image rush over them as it transitions to the next. His work is often discussed in relation to the aesthetic and tone of online video, chat, and internet culture, as if it seeks to represent the hyper-accelerated nature of these technologies.

David Karp is the founder and CEO of the popular microblogging platform Tumblr. Tumblr was created in 2007 as an alternative to traditional long-form blogging. Karp wanted to produce a format that allowed users to post images, quotes, video, and other short items throughout the day, creating a constant stream of short-form content. Tumblr has grown into an extremely popular blogging platform, with an average of 2,000,000 posts and 15,000 new users per day. -J.G.

10 Ijsselmeerdijk, Zeevang, Nederland, 2010 – Digital C-print

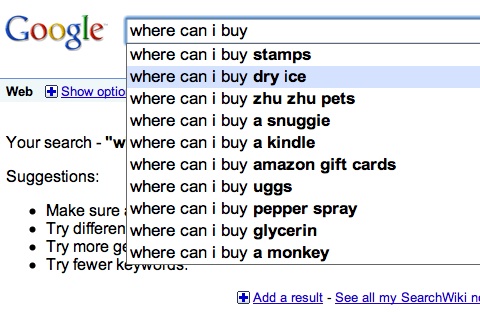

The use of search engines and other online services involves an implicit transaction: You benefit from a company’s software, and the company benefits from the information left in the wake of your surfing. User compliance relies on the trust that this information won’t be abused, and compliance continues because, in most cases, the chances of abuse seem trivial. Whether you embrace this reality or feel resigned to it, you have to admit that internet companies have introduced a dramatic paradigm shift with the proposition that everyone’s preferences and interests belong to the commons, as public as streets, parks, air, and water. Google added a brazen twist to that idea in 2007, when it dispatched a fleet of camera-equipped cars to photograph every public place in the world, in order to add a new feature—Google Street View—to its popular application, Google Maps.

Jon Rafman has spent countless hours exploring the world through the window of Google Street View, saving striking images from the service’s panorama of stitched-together snapshots. The images displayed here represent his collection’s range of sights and moods: a burning house on an eerily unpopulated Arkansas street, which the Google vehicle passes with utter detachment; teenage boys in Northern Ireland, their faces automatically blurred in Google’s gesture toward privacy, even as they make gestures of their own at Google; the haunting, cinematic shot of a spectrally pale woman alone on a beach. Rafman has compared his work with Google Street Views to that of classic street photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, who sought out moments of urgency and serendipity. If Google’s mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” then Rafman

has decided that his is to make it meaningful. -B.D.

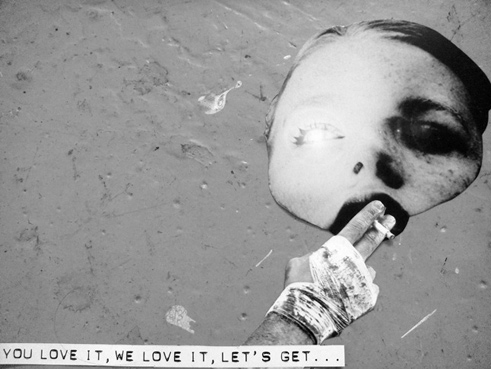

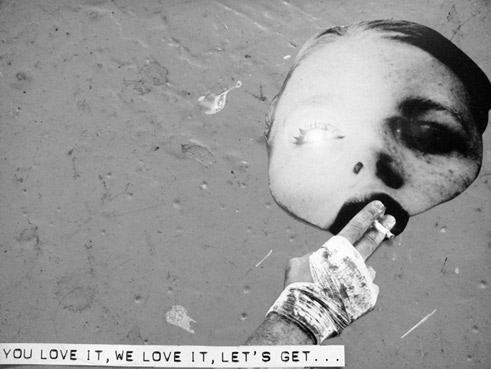

2009 – 27 Inkjet prints on silver foil

Clunie Reid prints out images found online, makes mixed-medium drawings with them, photographs the results, and prints them again. Her method is like a semi-manual version of Photoshop, where contact between the artist‘s hand and the digital image is an essential part of the process. Reid often flips images on their side or head as hammy suggestions of failure and disaster, or articulates her point with crude scrawls of a marker. Sometimes she does both. Binary thinking and sentimentality are objects of scorn for Reid, and she exaggerates their simplicity by layering them to the point of absurdity. Her techniques of re-photography and reprinting are formal doubles to these quasi-literary devices of rephrasing and reiteration.

Reid describes herself as a “complete amateur online” yet her work demonstrates a true sensitivity to the condition of the digital image. She reuses certain images within a series, or even across several works. The silver foil she

uses to print her collages adds an element of indeterminacy and fluidity as it captures the shifting color and light of the gallery where the work is displayed. Among other features of Reid‘s work, these speak to the overwhelming sensation of navigating a loosely managed, chaotic environment.

Education

Royal College of Art, London. MA Painting, 1993- 95

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, USA, 1994

Wimbledon School of Art, London. BA Painting, 1990- 93

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Dumb Down, Get Dressed, Move Out, Studio Voltaire, London. Supported by The Elephant Trust, London

2010 – Clunie Reid and James Richards, Art Now, Tate Britain, London.

2010 – In The Event Of Suspicion, Bielefelder Kunstverein, Germany

2010 – Newspeak: British Art Now, The Saatchi Gallery, London

2010 – Contact Photography Festival, Toronto

2010 – Misty Boundaries Fades and Dissolves, Fromcontent, London

2009 – Zoo 2009, John Jones Prize Winner Exhibition, London

2009 – Clunie Reid, MOT International, London

2009 – Out There, Not Us, Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea

2009 – Peek A De Boom, Galerie Reinhard Hauff, Stuttgart

2009 – Karaoke – Photographic Quotes, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Zurich

2009 – We Came Here To Get Laid, Not To Critique Dutch Culture, with Tom Ellis and Richard Parry, Wilfried Lentz, Rotterdam

2008 – Nought To Sixty, Institute for Contemporary Arts, London

2008 – Life As You Like It, Camden Arts Centre, London

2007 – Life As You Like It, MOT International, London

2007 – East International, Norwich

2007 – Propaganda Machine, Local Operations, Serpentine Gallery, London

2007 – Transmission Gallery, Glasgow

2007 – Aspen 11, Neue Alte Brucke, Frankfurt

2006 – Trousers Too Tight, Heels To High, Keith Talent Gallery, London

2006 – A Tree Can’t See, Flaca Gallery, London

2006 – Launch Project, “falkeandcharlotte project space”/Dolores, Ellen de Bruijne Gallery, Amsterdam

2006 – Needle Drops, Parade, London

2006 – God Is Bored Of Us II, Fast Moving Consumer Goods, London

2006 – This Show Is Ribbed For Her Pleasure, Cynthia Broan Gallery, New York

2005 – Les Marveilles Du Monde, Centre for Contemporary Art, Dunkerque

2005 – Clutterin Colours Roamin In Limbo, Keith Talent Gallery, London

2004 – Doubtful Pleasures, APT Gallery, London

2004 – Sir Reel, Redux Gallery, London

2004 – The Possibility Of Experiencing The Death Of Others, One in the Other Gallery, London

2003 – Render Red Nose, MOT, London

2003 – Not Everything, Jeffrey Charles, London

2003 – Other Than, MOT, London

2003 – Platform Primera, Plate forme 4, Dunkerque

2003 – The Greatest Show On The Earth, curated by Peter Fillingham, The Metropole Gallery, Folkestone

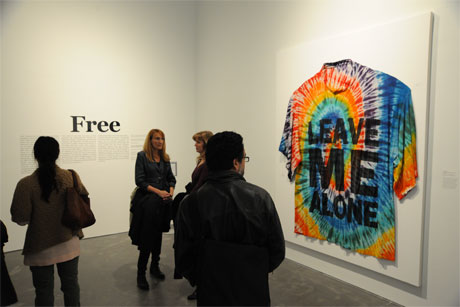

THE SKIES THE LIMIT (LEAVE ME ALONE) – 1998–2009 – Hand painted, rainbow tie-dyed T-shirt, acrylic, graphite, and oil pastel on canvas

YOU AND ME FINDINGS (ROTATED 90° CW) – 2009 – Black gesso on canvas, lot of 109 vintage and newer small earring singles

Seizure – 2006 – Inkjet print on PVC foam board, two aluminum saw horses

Double Feature #2 – 2010 – High-density foam, fiberglass resin, urethane primer, vacuum metalized in gold

The image search engine has upended cliché by teaching its users that a word is worth a thousand pictures. Of course, pictures retain their unique communicative properties, but in the context of the internet access to them is determined by language. Amanda Ross-Ho’s work with images found online plays off the relations between visual and verbal modes of representation. Ross-Ho is interested in eBay as a platform that not only translates generalized keywords into concrete objects, but also includes a framework for acquiring those objects. For her 2009 YOU AND ME FINDINGS (ROTATED 90° CW), she collected the earrings she had purchased on eBay through searches for “earrings,” and placed them on a canvas, where they lost their function as jewelry and became abstractions, like the word “earrings” itself. Double Feature #2, a fabricated enlargement clown-head pin, performs the same action but uses scale instead of plurality as a means of conceptual transformation.

Seizure began with a collection of photographs of confiscated contraband that Ross-Ho had printed and laid on a table in her studio. As she arranged the images, the logic of her collection began to duplicate the organization of objects within the photos. By photographing the surface of her table and incorporating it in a sculpture, Ross-Ho took the images she “confiscated” from police websites—seedy, rarely seen corners of the internet—and recoded them for public consumption in a dramatically different context.

The dates indicated for SKIES THE LIMIT (LEAVE ME ALONE)—1998–2009—reflect a lengthy process of metamorphosis and cannibalization. LEAVE ME ALONE, a work Ross-Ho made in 1998, was an extra-large T-shirt hung in a gallery as a meditation on clothing as a vehicle for a message and size as a correlate of volume. Later, she merged a photograph of that work with an image of tie-dyed T-shirt. Most recently, she tie-dyed the T-shirt purchased in 1998 and mounted it on a canvas, as a way of “printing” her preceding Photoshop experiment. SKIES THE LIMIT involves a potentially endless process of versioning and recontextualization, which mirrors the nature of her sources.

Education

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, Master of Fine Arts, 2006

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Bachelor of Fine Arts, 1998

Exchange Program: California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA, 1997

Selected Exhibitions

2011 – The Approach, London, UK

2011 – Visual Arts Center, University of Texas, Austin, TX

2010 – Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles, CA

2010 – SOMEBODY STOP ME, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, NY

2010 – Project Series 40: Amanda Ross-Ho, Pomona College Museum of Art, Pomona, CA

2010 – New Photography 2010, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

2010 – The Artist’s Museum, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA

2009 – UNTITLED EVENT, Hoet Bekaert Gallery, Gent, Belgium

2009 – Interiority Complex, Artist Curated Projects, Los Angeles, CA

2009 – Bitch is the New Black, Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2009 – Summer Group Show, Mitchell-Innes and Nash, New York, NY

2009 – July Artist of the Month, Invisible Exports, New York, NY

2008 – HALF OF WHAT I SAY IS MEANINGLESS, Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles, CA

2008 – Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

2007 – Hoet Bekaert Gallery, Knokke, Belgium

2007 – NOTHIN FUCKIN MATTERS, Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles, CA

2006 – gran-abertura, Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL

2006 – Don’t Front (You Know I Got Cha Open), Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles, CA

2004 – Season Finale, Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL

2003 – The Earth is Rotating with this Room as its Axis, Soap Factory, Minneapolis, MN

2003 – Scene of Changery, Dogmatic, Chicago, IL

2010 – Multimedia installation

Despina, the Toaster, is a strident feminist. Sergei, the bleach bottle, is a lecherous Marxist—or rather a neo-post-Marxist, as he insists on calling himself. Tape players Lucian and Osmin are opinionated intellectuals. In Alexandre Singh’s comedy of manners, the personalities of the characters are as one-dimensional as their bodies are immobile. His allegorical device helps fix them in the audience’s mind as their conversation spins out on vertiginous loops and wild tangents, loosely centered on a debate of the merits of The School for Objects, an installation by Alexandre Singh almost identical to the one that viewers encounter here. The School for Objects Criticized inverts the roles of artwork and spectator by letting sculptures speculate on the world of humans. Their bombastic utterances on art cast doubt on our own discussions of art and culture, on the contradictory and ill-considered ideological criteria we often use to judge the worth of art

Singh‘s work refers to the self-aware theater of Molière (the title of this work and the unrealized one discussed therein riff on The School for Wives and The School for Wives Criticized) and the satirical writings of Lucian Samosata, the tape player’s namesake, who in the third century parodied both the Socratic method and the waning Roman pantheon in dialogues among impotent deities. Influences of Oscar Wilde and Woody Allen can also be felt. Singh’s collages, performances, and installations draw connections between works and ideas of disparate periods to position culture as a continuous field of playful, reflexive thought, rather than a sub-segment of civilization that develops linearly, determined by changes in technology and politics. The School for Objects Criticized connects to themes of “Free” in its desire to move against the prevailing winds of change, expressed in the use of an outmoded genre—the theatrical comedy of manners—to mock aspirations to articulate the essence of our age. -B.D.

Education

Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ME, 2006

School of Visual Arts, New York, NY, 2005

Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford University, UK, 2001

Selected Exhibitions

2010 -The School for Objects & The School for Objects Criticized, Monitor Gallery, Rome

2009 – 3 Lectures + 1 Story = 4 Evenings: Performa Biennial 09, White Columns, New York

2009 – Assembly Instructions (Tangential Logick), Harris Lieberman Gallery, New York

2008 – Assembly Instructions, Jack Hanley Gallery, San Francisco

2008 – The Marque of the Third Stripe, Monitor Gallery, Rome

2008 – Hello Meth Lab in the Sun, Alexandre Singh, Justin Lowe & Jonah Freeman in collaboration, Ballroom, Marfa, TX

2008 – UNCLEHEAD, Alexandre Singh & Rita Sobral Campos in collaboration, Museu da Electricidade, Lisbon

2007 – The Marque of the Third Stripe, White Room, White Columns, New York

2010 – Bold Tendencies IV, Peckham Rye Multistory Car Park, London

2010 – Bagna Cauda, Art:Concept, Paris

2010 – Voices from Silence – Truths Unveiled by Time, Opdahl Gallery, Berlin

2010 – Acts Are For Actors, Southfirst Gallery, Brooklyn

2010 – Dynasty, Palais de Tokyo & Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris (cat.)

Arrivals and Departures_Europe, Mole Vanvitelliana, Ancona, Italy

Knight’s Move, Sculpture Center, New York

2010 Fax, Para/Site Art Space, Hong Kong, Plug In ICA,

Winnipeg, Canada and Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA

2009 100 Years (version #2), PS1-MoMA, Queens, NY

Fax, Contemporary Museum, Baltimore

NO SOUL FOR SALE, Rhizome at the New Museum, X-Initiative, New York

2010 – Plastic, acrylic, glass, and spray paint

Critic and novelist Bruce Sterling has said, “The idea that the virtual is somehow philosophically separate from the actual is a period notion. It’s done.” Encompassing websites, video, collage and sculpture, Harm van den Dorpel melds physical and virtual realms, exploring how their overlap affects aesthetics and objecthood. He often utilizes sophisticated design and programming to create works that return materiality to digital form.

For the series “Redux,” van den Dorpel appropriated movie posters from popular Hollywood films, including Cloverfield, The Lost World, and King Kong, which rely on costly technologies to create spectacular digital effects. These are the same technologies that are later used (by non-industry professionals) to capture and distribute the films for free via peer-to-peer networks and on CDs and DVDs. The collages in “Redux” are inspired by this radical shift in form. They draw on the commercial branding of the DVD-R & CD-Rs to examine the way content is carried in a post-cinematic, sometimes illegal state, where packaging and presence has been completely stripped down. By removing all figurative elements from the original posters and adding other material such as plastics, acrylic, glass, and spray paint, the collages lose their primary narrative and commercial context. What remains is a vastly different object, abstracted from its original, relying almost entirely on pattern and texture to convey a complex media transition, that is totally unlike, but haunted by its original content. -J.G./L.C.

Education

Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam, Fine Arts, 2006

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Artificial Intelligence, 2001

Selected Exhibitions

2010 – Multiplex, Peer to Space, Munich, DE

2010 – Enchanted, School of Development, Berlin, DE

2010 – Fotografia, Museum of Contemporary Art, Rome, IT

2010 – Sousveillance, The Young Artists’ Biennial, Romania

2009 – Homebrew Readymades, Senko Gallery, Denmark

2009 – Prints, etc., Fabio Paris , Brescia, IT

2009 – Contemporary Semantics Beta, Arti et Amicitae, Amsterdam

2009 – OAOA Annual Show, Rijksacademie van Beeldende Kunst, Amsterdam

2009 – Are you sure you are you?, Spencer Brownstone Gallery, New York, NY

2009 – The New Easy, Art News Projects, Berlin, DE

2009 – New Wave, Internet Pavillion, Biennale di Venezia, Venice, IT

2009 – Away from Keyboard Sculpture Garden, Atelierhof Kreuzberg, Berlin, DE

2009 – Argot, Plan B, Amsterdam

2009 – Objects, Furniture, and Patterns, Art Since The Summer Of ’69, New York, NY

2009 – Versions, Dutch Institute For Media Arts, Amsterdam

Essays

Essays by Lauren Cornell, Joanne McNeil, Brian Droitcour, Ed Halter, and Caterina Fake will be published sequentially throughout the run of the exhibition.

The palest ink is better than the strongest memory.

— Chinese proverb

In 2001 the hard disk on my laptop crashed and everything on it was lost. I’d been using the computer for two, almost three years, and had all my work on it—email, which was stored locally; photos; fragments of poems; presentations; sketches; ideas; love letters; everything. I lamented the loss to my friends and got lectured on doing backups. I sent the disk out to be repaired, but word came back from the shop that there was nothing that could be done. Miserably I thought of all the precious memories I’d lost.

Days later, after the initial shock had passed, I had a sudden sense of liberation and relief. 1999-2000-2001—I was completely free of those three years— I had no archive.

Recently I tried to recover some old blog posts from 1998–2003, and found they were also gone. I went to the Internet Archive’s Way Back Machine, but it turns out at some point I’d blocked the Archive on my robots.txt. And I remembered the impulse that inspired the blocking: the ruthlessness of computers and how, if you set them up a certain way, the way that has become, today, the default— they never, ever forget.

Several years later, I started a website called Flickr and a team of people in Canada, a site for digital photographs, shared among a social network, with the photos defaulting to a public view. It incorporated tagging, groups, an API, posting photos on other sites, and other features that have now become standard in social media. It grew very rapidly, and as one of my friends told me, Flickr was a really great place to be a photograph. A photograph could remember the name of the wine you liked at that restaurant, that brunch where your friend made the funny jokes, the slant of sun on a winter’s day, your lover’s face that morning in May. We’d improved ourselves by improving our recall, our memory.

One of the first users of Flickr was a guy who seemed to photograph every minute of every day. Untied shoelaces, spots on the pavement—nothing seemed too trivial to escape his documentation and attention. This is excessive, even pathological, I thought. But it was nothing like what was to come. The participatory media of Web 2.0—MySpace, YouTube, Flickr, Facebook, Twitter, and so on—made documentation, sharing, deliberate and passive documentation a daily activity for billions of internet denizens, including businesses, governments, and citizens.

“Free” is the museum show of our times, presaging the whole Wikileaks dustup, and it shows shifting power dynamics and a glimpse of the human in a world of flowing data. Pervading the show is this sense of how the “data”—the “facts,” if you will—tells us something, but fails to capture the human drama, the story, the suffering, the lived lives behind the information gathered and displayed.

Lisa Oppenheim gathers photographs that American soldiers stationed in Iraq have taken of Iraqi sunsets and posted on Flickr, prints them, and then holds them up, re-photographing against her own, local sunsets in an act of tribute and attempt at communal experience. The gulf yawning between her experience and theirs, the impossibility of connection, is emphasized. The sense is that their lives in a war zone cannot be known, and only a gesture is made to demonstrate fellow feeling.

Images of people caught on Google Maps “Street View” appear in Jon Rafman’s work, of which Rafman says:

The world captured by Google appears to be more truthful and more transparent because of the weight accorded to external reality, the perception of a neutral, unbiased recording, and even the vastness of the project.

We are bombarded by fragmentary impressions and overwhelmed with data, but we often see too much and register nothing.

Although the Google search engine may be seen as benevolent, Google Street Views present a universe observed by the detached gaze of an indifferent Being. Its cameras witness but do not act in history. For all Google cares, the world could be absent of moral dimension.

Joel Holmberg collects earnest, whimsical and profound questions on Yahoo! Answers, foregrounding their often earnest, whimsical, and profound responses. They are both mock-serious and mock-comic in attitude, showing, again, the gap the medium creates between the querent and the human truth. Martin Hendrick’s video of shockingly callous texts (LOL!!!) in response to the footage of Saddam Hussein’s execution shows how people become things, how digital experiences are reduced to entertainment, and how meaning is leached out of the most significant or fraught events. It’s impossible not to see how the anonymity of online interactions dehumanizes us.

This effect is nowhere more tragic than in the real-life suicides of various teenagers living their lives online: Tyler Clementi, a freshman at Rutgers University, was having sex with another guy when his roommate and a female student broadcast their intimacies on the internet, resulting in Clementi throwing himself off a bridge and killing himself. Abraham Biggs, a young nineteen-year-old man from Florida, committed suicide live online, on the “lifecasting” site Justin.tv while viewers said “go ahead and do it, faggot.” And Megan Meier, a thirteen-year-old, hung herself after her rival’s mother created a fake MySpace identity “Josh Evans” to bully and humiliate her.

Can you withdraw? Can you escape? Is it possible to exist without being recorded by people’s devices, the unscrupulous roommates who would broadcast our most intimate moments, not to mention the ubiquitous closed-circuit cameras? Writer Evan Ratliff conducted an experiment for Wired magazine, in which he attempted to vanish for thirty days. His data trail was collated by various self-anointed online detectives (a $5,000 prize was offered to the person who could find Ratliff, say the word “fluke,” and take a photo of him) and he was eventually found. The sheer difficulty and inconvenience he underwent to attempt to evade detection was a lesson to us all. The project has launched an entire movement of efforts to disappear.

”Free” includes Jill Magid’s work Becoming Tarden (2010), a book-length profile of 18 Dutch secret service agents, created in collaboration with the agency. The final product did not meet the agency’s approval, and 40% of the text was censored — to protect the agents and the agency, to permit them secrecy, to allow their work to continue, as a secret service agency does, in private. Many arguments against the release of documents by Wikileaks covered the same territory: is some level of privacy required for diplomacy to take place? Not secrecy, mind you. Privacy. All of our parents had to do something in order for us to be conceived and born. It’s not a secret. But it likely happened in private. A necessary distinction.

Becoming Tarden is exhibited at the New Museum, copies of the book printed with the text blacked out, hiding the any information that might identify the secret service agents. Did their real selves escape behind those black boxes? You get the feeling it was never there to begin with. The book’s final quote is from Jerzy Kosinski’s Cockpit, where the character “Tarden” appears:

All that time and trouble, and still the record is a superficial one: I see only how I looked in the fraction of a second when the shutter was open. But there’s no trace of the thoughts and emotions that surrounded that moment. When I die and my memories die with me, all that will remain will be thousands of yellowing photographs and 35mm negatives in my filing cabinets.

The works of art in “Free” show the gap between the impassive data-gathering technology, human input, and the strange hybrid that is result of those interactions. As the human and data combine, as we appear in surveillance cameras, and leave behind traces on the internet, we’re in an alien netherworld, our selves and our humanity fugitive beyond the machine. There’s a reason we say IRL: our real life happens offline, unrecorded.

I often wonder if we should build some kind of forgetting into our systems and archives, so ways of being expand rather than contract. Drop.io, an online file sharing service, allowed you to choose the length of time before your data would be deleted. This seems not only sensible, but desirable. As Heidegger said, in Being and Time, “Forgetting is not nothing, nor is it just a failure to remember; it is rather a ‘positive’ ecstatic mode of one’s having been, a mode with a character of its own.” Proustian memory, not the palest ink, should be the ideal we are building into our technology; not what memory recalls, but what it evokes. The palest ink tells us what we’ve done or where we’ve been, but not who we are.

If we are not given the chance to forget, we are also not given the chance to recover our memories, to alter them with time, perspective, and wisdom. Forgetting, we can be ourselves beyond what the past has told us we are, we can evolve. That is the possibility we want from the future.

I remember a quote from the pre-digital, offline version of my high school yearbook, more than 20 years ago, which seems impossibly cute and corny to me now (form is more difficult, capitalization more dignified!) and yet so very true:

teach disappearing also me the keen

illimitable secret of begin

— e.e. cummings

Charles A. Csuri, Hummingbird II, 1969

A little over forty years ago, Harold Rosenberg observed that contemporary painting and sculpture had transmogrified into what he called “a species of centaur–half art materials, half words,”1 a hybrid form in sharp contrast to the visual purity of the previous decade’s central artistic movement, Abstract Expressionism. Though Rosenberg himself had coined the term “action painting,” originally arguing for that mode’s existential ability to convey a record of the artist’s process on the canvas (“not a picture, but an event”2 as he put it), by the late 1960s he had evidently revised this theory in light of conceptual art, minimalism, earthworks, and other developments.

Modern art, he now argued, never truly offered such direct access to experience; from its earliest beginnings, it had required the support of language, in the form of artists’ writings, curatorial statements, and criticism, in order be understood. Experiencing the artwork itself had become insufficient; increasingly, specialized knowledge was required. “Of itself, the eye is incapable of breaking into the intellectual system that today distinguishes between objects that are art and those that are not,” Rosenberg maintained. “Given its primitive function of discriminating among things in shopping centers and on highways, the eye will recognize a Noland as a fabric design, a Judd as a stack of metal bins—until the eye’s outrageous philistinism has been subdued by the drone of formulas concerning breakthroughs in color, space, and even optical perception (this, too, unseen by the eye, of course).”3 Rosenberg imagines that for viewers without access to these “formulas,” contemporary art objects simply disappeared into the consumer landscape, seen but misunderstood.

Rosenberg suggested that the vogue for text supporting the works themselves—or in the case of the most uncompromising conceptual artists, text as the works themselves—was not a radical break with the past, but an intensification of certain pre-existing qualities. The conceptual turn was simply a more overt manifestation of a state of affairs that stretched back to the turn of the century, when the pictorial role of art was displaced by the full-scale rethinking of visual representation at the core of the various avant-gardes. Modern art had always been conceptual; in the 1960s, it just became more self-aware about it.

In the headiness of this realization, artists and critics foresaw the dematerialization of art, but this never completely happened. Today, gallery spaces of the early 21st century remain populated by Rosenberg’s word-object centaurs. Once pressed into battle against the primacy of painting and sculpture, they have evolved into less warlike beasts, a menagerie of possibilities roaming through the expanded field. Like figures from Ovid, they exist frozen in mid-transformation from one state to the next.

“Free” is dominated by work in a post-conceptual mode that Rosenberg would recognize; it is a show in which wall text matters, and post-visit googling rewarded. Most pieces, like Aleksandra Domanovic’s 19:30 (2010), Lisa Oppenheim’s The Sun Is Always Setting Somewhere Else (2006) or Amanda Ross-Ho’s YOU AND ME FINDINGS (ROTATED 90° CW) (2009), remain less than fully comprehensible without recourse to information about their making. An uninformed viewer could not know that Domanovic collected a personal archive of Yugoslavian nightly news intro segments, then distributed them online for DJs to use as samples, simply by watching her two-screen video, though some variation of this back-story might be surmised. A similar issue arises with Ross-Ho’s grid of gold earrings, arranged on black canvas. She displays this jewelry like a taxonomist attempting to catalog variations within a species, but nothing intrinsic to the resulting arrangement communicates how she sourced them on eBay using the keyword “earring;” with this knowledge as context, her piece looks more like a physicalized version of a search results listing. At first glance, Oppenheim’s slides show photographs of sunsets re-photographed against other sunsets, their horizon-lines synched up by the photographer’s hand. The work only becomes truly meaningful when one reads that she found pictures of evenings in Iraq, taken by American soldiers and uploaded to Flickr, then re-shot them against analogous views in New York.

Cursory museum-goers averse to reading would mistake these works for simply what they appear to be: a video installation of appropriated television logos and rave footage, a minimalistic grid of found earrings, a slideshow of reflexive landscape photographs. Each of these objects is epistemologically incomplete, reliant on exterior information to achieve full significance. They point beyond themselves, to events that occurred outside the gallery walls, but at the same time bear more formal integrity than mere props for ideas.

This quality of incompleteness, of meanings sequestered elsewhere, is by no means unique to the works in “Free”—innumerable examples could be cited from the past half-century. But by focusing on art that responds to the Internet, something new comes to light through this exhibition. If conceptual art is a hybrid of objects and ideas, then conceptual art has changed, because our relationship to ideas has changed. And our relationship to ideas has changed because of the Internet. The Internet has altered how we relate to ideas—how we discover them, how we distribute them, how they circulate through society, how they are hidden or revealed—and this plays out in the latter-day descendants of what Gregory Battcock called “idea art.”